Welcome to the website of the Peralba farm, owned by AROS AGRICOLA.

About Us Peralba Farm

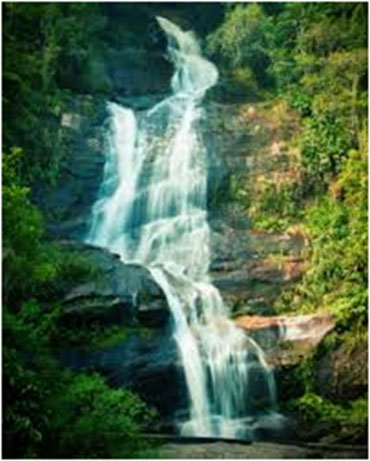

Here you can see the beauty of this wonderful land and the result of more than twelve years of efforts to protect this forgotten corner of primary Atlantic Rainforest. Over the years, not a single tree was cut, hunting has been banned and the fauna protected by a severe and active forest-guardian; even fishing has been suspended to preserve the environment.

Here you can see the beauty of this wonderful land and the result of more than twelve years of efforts to protect this forgotten corner of primary Atlantic Rainforest. Over the years, not a single tree was cut, hunting has been banned and the fauna protected by a severe and active forest-guardian; even fishing has been suspended to preserve the environment.

The results are now evident: deer that were rarely seen before are reproducing in the area, small jaguars live and hunt freely in the territory and countless birds are restocking the forest. The results are now evident: deer that were rarely seen before are reproducing in the area, small jaguars live and hunt freely in the territory and countless birds are restocking the forest.

The results are now evident: deer that were rarely seen before are reproducing in the area, small jaguars live and hunt freely in the territory and countless birds are restocking the forest. The results are now evident: deer that were rarely seen before are reproducing in the area, small jaguars live and hunt freely in the territory and countless birds are restocking the forest.

The choice to invest in limes was not casual: statistics were carefully analyzed, the various links in the chain of value, export containers purchased from third parties to verify the import and distribution difficulties in the Netherlands and in Italy. We did our homework before we committed to any investment of businesses: the historical series heralded a steady growth in the last 15 years (3%) While the future projections of consumption have never been assessed at no less than 6% for 5 years in the future.

News

Who We Are

The limes business

This major activity is divided into several segments:

Exportof packed fruit in containers to AROS TRADING CO. in Holland

Export of packed fruit in containers to receivers in Holland or directly anywhere in the world

Selection and packing of fruit for third parties

Sale of fruit in nature to other producers, farmers, packers or owners of packing houses, in Bahia or other states

Sale of processed fruit (sterilized and waxed) to other local packers or distributors

Sale of processed fruit to orto-fruit market in Salvador

Sale of selected and processed fruit to supermarkets

Sale of rejected fruit to juice producers

Segment 1 and 2 are linked to annual supply programmesto our own clients and to our main receivers in Holland. This practice allowed us to develop our own brands in the Europe markets, particularly in Germany and Switzerland.

Segment 3 serves clients in periods when we have excess fruit and independent exporters contract with us the supply of containers size orders.

Segment 4 allows us to supply friendly producers to complete consignments or even to integrate their delivery programs when events impeded them.

Segment 5 is an important outlet to wholesalers for fruit that did not pass the export quality test. As we are focused almost exclusively to export, such activity is a major contributor to costs.

Segment 6 refers to our sales to get a boost in the Salvador fruit market, SEASA, which is then distributes to retailer all over the city

Segment 7 are sales directly to supermarkets. We do pursue such opportunities in spite of the difficulties of such a business, as the supermarkets are highly demanding andfinicky to quality and reliability of deliveries

We keep sales of smashers to its absolute minimum, but a small percentage of our fruit, unfortunately, is delivered to this market.

The sales responsibilities are also divided between two departments: internal and export sales.Accounts are centralized.

It is difficult to give dimensions to each segment in both quantities and value as vagaries of weather and prices are a constant. On average, the price per carton in Holland varies between €5.65 and €7.58 during any one year. However, there have been periods when the price shot up to €12.00 to €15.00, as in 2016 in a period of nearly three months, from April to June that year. Due to an exceptional el Niño effect, Mexico stopped production and Brazil ran out of limes. We shipped most of our production right in that period it was … cool.

As our understanding of the business grew, in the last years we focused aggressively on quality. The results from interventions aimed at improving quality show only 18 months later: Only then its effect are shown. As our export is the main driver of the business, we reached 86% utilization in 2016! 86%!!! Four years of concentrated effort on rising quality did that feat. Most other producers are happy when they reach 50% to 60%… we aim at 90% in 2017!

This is a major element of our success and of our pride in this business. Our clients confirm this by demanding our product, buying full containers before they docked in Amsterdam and even wait till we ship our fruit. Good for the ego and the pocket as well.

The Coffee Business

This business is by far simpler that the limes and concentrates mainly in the husbandry of the plantation. We have a good relationship with four ‘torrefadores’ which buy our full production without flinching. Because of the maturity of this market, prices are set in Chicago and New York and filter down easily to the producer.

We produce the Arabica strain (28% with 192 sacs in 2011) and Robusta 72% with 490 sacs). The goal for 2017 is exactly double these volumes.

Here again prices vary daily, but the average of between US$1.39 and US$1,68 per pound in the Chicago exchange market. These values translate into a R$250.00/R$320.00 in Bahia, when the exchange rate to the Brazilian Real was 2.15 to 1 US$. In 2016 the exchange rate averaged R$3.5 and even reached the level of R$4.13 for several months. During that period the price of a sack of Arabica shot up to R$800.00, and R$660.00 for the Robusta quality.

Our other business: the short life cycle produces

Eucaliptus

Cacau

Açaí

Dendê

Seringa

The eucalyptus business

We have 35 hectares of eucalyptus trees 8 years old, ready for cutting. We can do that and also expand another 50 to 60 hectares. In this way, in four to six years, we shall have 85 to 95 hectares of grown eucalyptus for sale.

There are plenty buyers in Valença, but it is always a fight to get a reasonable price. We are approaching steel mills to try and sell wood directly to them, but that will demand culling and preparing abilities that we do not have.

The eucalyptus business

Still, even at current prices for the buyer to come and cut and take away is complicated, prices vary between R432 and R$45 per cubic meter. Converted in tons, prices vary from a low low of R$3000.00 to an average of R$5000.00 per ton, while one hectare produces at least 35 to 50 tons. The nice part is that we did not spend a dime for the first six yearssince we planted the first tree. Manpower zero. It is a business of great expansions. For us, it is a nice income which can be managed, year after year, by, culling grown trees… and planting a new one to increase the volume. 95 hectares sounds good.

The cacao business

We do not have much cacao, maybe 15 hectares dispersed in various areas of the farm, mainly near streams or wet spots.

The three hectares near the Yellow House produced nearly three tons in 2013. Sold at R$260.00 per arroba, gave to buy a small car. The potential is not really on cacao by itself, but in husbandry with rubber trees.

That is very much in our minds.

More below, when we shall talk about the seringa plantation.

The acai business

In 2010 we planted two hectares to experiment with this crop near the Yellow House, more out of curiosity than a real intention. The growth was so energetic that we planted another couple of hectares in another wet area, far away, and left it to grow unattended. Same result: exceptional growth, total resistance to pests, no fertilizer, no husbandry, nothing. As this palm grows in very humid environments, and we have plenty of those around the farm, maybe we could fill those remote areas with this crop. We estimated that we might fill 30 or 40 hectares in various sites. Harvesting could be done on partnership with some local, a la piassava, and costs would be kept at a minimum. Several smashers confirmed their interest in buying all we could produce… small income in comparison with limes, but nice to have, without all the headaches of a full plantation of this produce. As soon as we get the limes stable, we shall revisit this crop. 2019 would be about the right time for this.

The dendé business

Dendé needs vast areas to become economically viable and for this reason, it will remain a minor/social crop to be harvested by our loyal Louro. He is a direct descendent of freed slaves and runs an extended family in a nearby area called Mata Escura, he is a neighbor of great value and presence, for whom we have great respect and affection. He and some members of his family (which includes his mother of 75 years of age) work at various times under contract in our coffee plantation. The dendé is totally harvested by him and we take a small cut to establish ownership. The rest is all for him.

Let’s call this our social investment in a precious neighbor.

The natural rubberbusiness (in husbandry with cacao)

The rubber business is serious business. It will probably be our next push in agriculture.

It has numerous advantages that make an investment in this area attractive:

Michelin, the tires manufacturer, has a latex processing plant about 35 km from the farm, it guarantees the purchase of the whole production and remunerates it at international levels

Michelin would supply us with selected genetic plants, specially adapted to our climate. It would provide free of charge specialized technical support throughout the plantation and growth. Would train our people in the latex harvesting techniques and in the correct husbandry of the plantation. Our investment would be in the appropriate land and a dedicated team.

Cacao is perfect for such a solution: the cultural tracts are very similar if not the same in many processes, use the same work force, and adds substantial revenue to the business. Our experiment in 2007/10 confirms the technical viability of such crop

The economics are simple: each rubber tree produces 2.2 kg. of latex per annum (based upon by historical record from Michelin itself). Each hectare produces 1350 kg of the staff per annum (again based upon decennial experience by

The best information of all, born of decades of experience by Michelin, is that 30hectares would be enough for an attractive economic return of approximately 34.2% ROI. Nice! We could start small and expand, as results would be warrant

Development banks are very favorable to such joint projects with big companies, particularly with Michelin, which has a long and successful history of such partnerships with locals. All this would be favorable in such circumstances.

The land is suitable, we have the work force ready, itis only to start.

When we integrate the cacao production, the issue gets even better: one hectare produces between 50 and 80 arrobas per annum and fetches the equivalent of US$3.100 per ton (average price in the New York stock exchange between 2010 and 2014). With all savings derived from tending to two crops at the same time, the breakeven has been calculated at 12 hectares. If well set up, in four years all this can become reality as it did in the past.

We have the perfect site in the extreme south of the farm that could receive the first 30 hectares. We could even start smaller if we wanted, say 10 or 20 hectares to start with. Expansion would come from buying holdings from nearby farmers who are going to sell as their subsistence farming is not viable anymore. The agronomists from Michelin already visited the area, took soil samples, pluviometry information, etc., and declared the area ideal for such a beginning. A friendly farmer, family really, who administered a rubber plantation of some 500 hectares, confirmed all previous information and added the idea of introducing a second crop, cacao, in husbandry with the rubber trees. The combined production would give very attractive returns

Michelin – see their publication ‘Assessment of growth and yield performance of rubber tree clones of the IAC 500 series’). Each liter of latex is sold at US$1.70, according to the Rubber Board of Malasia, which establishes the worldwide price for this produce.

The pawpa business

Growing pawpaw is very profitable. In our case, by planting it in husbandry with limes, it was a success: leaf spraying and pest control are almost identical for both crops.

Unfortunately, this can be done for the first three years only, as the limes then start producing and spraying and must abide to MRL limitations. Synchronizing intervention becomes difficult and dangerous. On the fourth year, impossible. Sometimes we can only spray one month before harvesting, and this becomes critical for the pawpaw.

Sadly, we stopped even before such issues crumpled our production: one has to consider that one hectare can produce up to 160 tons of fruit and the market is close! It is 68km away and Salvador buys everything we can produce! Prices too are attractive: we expected an average of R$0.60 per Kg (approximately US$0.40 per kg at the exchange rate of that year). In 2011 we hit R$1.12 per kg! That was a BIG bonus that year!

We stopped the practice in 2013. In 2014, on the occasion of planting Peralba Sucupira, we considered planting in husbandry again, but we balked, as we adopted a super dense method for the limes and we were weary of possible ill effects in such a new environment.

We will wait for 2018. We already looked at several areas where we can plant this crop away from other produces and concentrate to obtaining bigger quantities… we even thought of buying a neighbors land to this end… we shall see. As we grow and consolidate the limes and coffee, we‘ll have the time and resources to do a serious business out of the papayas.

The passion fruit business

The maracujá replicates the rationale of the papaw: a culture of easy handing, low cost and high profit (particularly when there is a draught and our microclimate protects us from it being ravaged.

The maracujá replicates the rationale of the papaw: a culture of easy handing, low cost and high profit (particularly when there is a draught and our microclimate protects us from it being ravaged.

Set in a commercial scale, its profitability is easily demonstrated: from one kg of selected seeds can be planted in nearly 10 hectares. Nurturing is almost nonexistent. Flower fertilization is made by hand by singing ladies. Selling prices vary from R$30 to R$60 (approximately US$20 to US$30, historically) per crate of 15kg.

Add to this a productivity of between 200 to 300 crates per hectares, and the equation becomes evident and profitable.

We are of the same mind as with the papaws: wait for the right moment and move in to industrial levels. Maybe even into a consortium with the same pawpaws … we shall see!

The watermelons and melons for export

E pela terceira vez caímos nas nossas limitações e tentações: foco no negócio de limão e lavouras consorciadas… e retornos interessantes.

Depois das experiências de 2010 e 2011, até pensamos de produzir essas frutas sozinha, numa plantação separada que incorporaria facilmente os melões de exportação, mas abandonamos a ideia quando das nossas prioridades em atingir uma qualidade superior na plantação de limão em conjunto com uma produtividade superior a 30 toneladas por hectare.

Similarly with melons for export. Our new partners asked for such a crop and would guarantee buying the whole production. The instability from South Africa was a concern for them to supply their customers.

Again we limited ourselves to successful experiments in favor of maintaining our focus on limes and coffee.

With watermelons we could have continued to plant every year. Just planting in between the limes lines would produce 30 to 50 tons per hectare, but it would demand difficult handling of spraying and crop husbandry. And the pest control would soon interfere with the limes. Not so much for the coffee, but we planted 5600 coffee trees per hectares and we feared the two cultures would compete and none would grow as expected… difficult decisions. Our leader, seu Wilson, predicted up to 80 to 100 tons per hectare, and even mentioned 140 under the right conditions. The math is easy. The market is nearby… focus, focus… and so we hesitated.

This experience was in 2009 and 10 was very favorable… and we were told we could even export to the USA. When we went back to the math, again the attractiveness appeared evident: a carton of 7 to 10 bushels of Melogold would pay between US$23 and US$25 (price in November 2015 for an 8 bushel carton).

In Europe, the similar kind, the Brazilian Queztali, would reap €0.75 to €0.85 per kg. (week 41 of 2015). Such prices would translate in US$32 for an 8 bushels carton. Allow a prudent 60 to 80 tons per hectare and the calculation is clear.

And with Mexico having weather problems the price would bring down the roof: US$58 in December 2015. It goes to show.

We have it all to make it, experience, climate, pest controls… the lot. We are watching this crop closely, avidly, for the right time to come!

The piassava business

This business is easy. Seu Josias does the lot. He calls us when the itinerant buyer stops to buy (we negotiate harder than he, as he tends to be anxious to sell fast and get his cash even faster…). In 2014 we sold some 40 tons of piassava. At R$40 to R$80 per arroba, it was a small but nice income.

Our cut is not major, but we are happy with it: 20 to 30 women from the nearby village, Camassandi, tend to the preparing of the fiber for sale. The cutting crew also is not small: at any time, every 18 months and for a period of 8 months we need labor to prune and transport the palm leaves to be processed.

The highest return is really with the maintenance of a good relationship with the locals. Their goods would be translated several times when we recruited packers for the packinghouse: we had plenty of volunteer and the selection is supported by a watchful seu Josias. Nice.

The ornamental flowers business

We are going to mention the growing of ornamental flowers as a potential business, on the escort of the success of the experiment of the Californian researcher. Maybe with a touch or regret and envy… or admiration.

According to him, quality and quantity achieved were exceptionally high for one simple reason: the flower was in its natural habitat, and all it needed was space and light to grow. Now we know.

The piassava business

If we invest just a little (as soon as we consolidate the limes and the coffee) to understand the peculiarities of this market, we can easily set up a special team to care exclusively of this produce. The economics mentioned are so steep that we hesitate to believe them: even if we cut them by half, it still is an extraordinary business.

We shall see… as soon as we are ready…

The Limes

The choice to invest in limes was not casual: statistics were carefully analyzed, the value chain links identified, containers purchased from third parties and exported to verify the import and distribution difficulties in the Netherlands and in Italy, just to mention few once the analysis was done.

We certainly did our homework before we committed any investment in this business: the historical series heralded a steady growth in the last 15 years (3% annual steady growth) while the future projections of consumption have never been assessed by several official and government bodies, at less than 6% for the 5 years into the future.

Our limes business went through two major cycles before we were sure that it was a viable and attractive business:

The initial phase of exploration of economic viability. We purchased fruit in Cruz das Almas, packed in local packing houses, exported to Europe, and then evaluated the costs and profitability of each link in the value chain. The productive potential of the future plantation is clear: its wide area climate, the microclimate in the South of the Recôncavo da Bahia, the quality of the soil, the absences of traditional pests, the negligible ecological impacts on the Atlantic forest and the possible effects of the proximity of the forest to the plantation.

This testing period lasted from 2006 to 2007.

In 2008 we planted the first 12 hectares in the Peralba Italia. Then 30 and finally 20 by 2010.

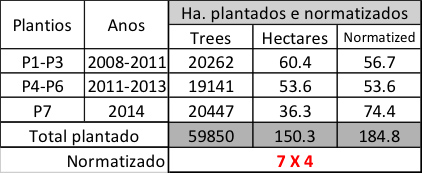

We call this new cycle the Aureus or Golden Period. The plantation and the limes business (or as some said our maturation in the understanding of the agro-business):meaning, we do not need to expand more above the approximately 160.3 hectares planted. This dimension would be an ‘optimum’ level of production and productivity without any marginal increase in costs: then we would normalize the whole plantation at a standard space of 7m X 4m per tree, we will reach an equivalent size of 196.1 hectares planted. This is plenty to make us independent from external suppliers and then not to incur in another steep increase in personnel and equipment. In other words: for the next five years (from 2017 to 2021) production levels will increase 584% from 2014 levels of 1200 tons/annum, while fixed costs will increase 28%!! It was a sort of pleasant discovery: till 2013 we had adopted all sorts of densities throughout the plantation, from 6m X 4m to 6m X 7m, 8m X 4m, even 8m X 7m, usually under the recommendation of a multitude of visiting ‘experts’.

In 2014 we planted 46.7 hectares at a 7m X 2m (and even 7m X 1m in certain patches. Our soil analysis confirmed that there was high fertility in older patches.). And since 2013, we replanted or substituted all nonproductive trees at 7m X 2m, and even 7m X 1.5m in some cases. When we compared such solutions with the productivity per hectare of the Brazilian standard of 7m X 4m, we realized that our standard density of 7m X 2m (that by 2017 will be in 95% of the plantation) and would bring us substantial gains: if the ideal productivity per hectare of the standard density of 7m X 4m is 30/35 metric tons per hectares, we could expect productivity levels of 52.3 tons per hectare or more, if we worked exceedingly well.

What does that mean? That we can export a minimum of 100 containers, starting in 2018, and up to 170 containers or maybe more by 2021. A lime tree lives on average between 16 and 32 years. We reached a plateau in costs that will increase by 3% to 5% per annum, irrespective of the volumes produced and after eight years, since 2008 our team is fully trained. We are achieving excellent efficiency and efficacy parameters (per hectare, per lot, per employee, per crate, per ton, per hour tractor, per man day or FTE, per Kg of fertilizer per Ha, per packed carton, per no of cartons packed per day per packer, per % utilization for export and we intend to maintain these KPIs, but we also intend to improve them, slowly and continuously

We feel we are doing well and will continue to do so, and will just keep on producing at least with the current quality.

We intend to work “always a little better” and “always a little further” than today.

A phase of consolidation. Between 2012 and 2016, we built and started operating our own packing house and became fully committed to the export business.

Initially all went according to plan. With the 2012 drought and the almost total disappearance of our supplies from Cruz and Mangabeira, we had to face a major decision: either to redirect our strategy to a major expansion effort and reach a level of production that would make us independent of external suppliers, or abandon the business. It became evident that our successful strategy would be to reach volumes that would allow us to commit to and fulfill delivery programs to our partners in the Netherlands: the damage from the drought had been minor (principally due to the innate resilience of the lime trees and to the characteristics of our microclimate). Rains returned that year (and even in that year we received almost 1500mm of rain!), and we acted immediately according to our new strategic posture.In that same year, 2012, we planted over almost 28000 trees in the Peralba Rio and Nova Rio. In 2014 we planted over 35000 new trees in Peralba Sucupira at densities of between 7m X 2m and 7m X 1.3m!.With a small investments in emergency irrigation, we prepared ourselves to survive any bad weather coming our way! We felt lucky and strong… and the following years confirmed such conclusions.Maybe we can add a mini second cycle to this period: the preparation of the farm for its full potential in what we saw as the emerging Areus (Golden) period of the Peralba Limes plantation. This mini cycle started in 2015 and will be completed by the end of 2016, then we will enter in 2017 with the whole farm in full production and with new investments in processes, management and ferti-irrigation! With this we would enter the following cycle.

It means that over the next few years we need:

- To sharpen our management (embracing the techniques of precision agriculture more’)

- To make better use of the computer tools (e.g. bringing real time processes into the field, particularly with the use of tractors)

- To improve our facilities (with bore holes to feed the emergency irrigation system already in place and introduce ferti-irrigation schemes, maybe even with subsurface dripping)

- To develop our key workers technically, teaching our tractor driver to use electronic instruments, send our field and harvest mangers to formal courses, technical development programmes at EMBRAPA, bring or institute field days led by specialized agronomists, etc.

- To open new markets in Europe, Canada and the Middle East

We can do all this, slowly, with caution and firmness: the team is good and is ready for these challenges.

We will act at the same time to improve the following area, in:

The Coffee

The choice of coffee as a profitable and successful investment also had a long maturation. We analyzed cocoa, rubber, ornamental flowers, biodiesel… thenwe finallycame to the conclusion that the coffee would be best suited to our environment, for the following reasons:

- Enabling environment: with 1800-2400 mm of rain annually, fairly well scattered throughout the year, the weather pattern indicated to be a favorable environment to certain species of coffee, mainly theconilon strain (Robusta)

- Topography: with the slopes of the first hills of the continental shelf, East-facing good fertile soil, several perennial streams and small lakes, high top-soil (>1m)

- Positive experience in nearby farms: on the South the coast of Dendê coast, on the outskirts of Valencia, 20 Km from the farm Peralba, the coffee has been grown extensively for hundreds of yearsManpower: with the proximity of other coffee plantations, it would be easy to find workforce with appropriate experience

- Attractive returns: a good coffee farm produces from 25 to 40 bags of green coffee per year; reaching the same goals, a return of 30% demonstrated a small, but viable and attractive businessBuyer’s market: the four toasters operating in the area of Santo Antonio assured us that they would buy all our production with ease, at ‘normal ‘ market prices

- Availability of funding: the Development Bank in Bahia have attractive credit lines to finance an investment of coffee

- So… in 2008 we entered the coffee production.

First, we had to decide where to plant.

The farm is relatively large and contains several appropriate places. Finally, we decided that it should be close to home headquarters and away from the limes plantationsso that no cross-contamination occurswith any pesticide or product carried by the wind. To ensure that our decisions were correct, the appropriate terrain (and countless other factors unknown by us at the time) we hired Dr. José Matiello, considered the highest coffee authority in Brazil. He guided us in the construction of nurseries (22 hectares he suggested a hotbed of 150,000 seeds), in the location of the sectors, in the design of the shed and dryers, on the machines … and millions other details.

… and we cared for it …

… and grow …

We became overwhelmed!!

… by the end of 2011 the coffee became a beautiful plantation!

… and they flowered intensely…

… and then in our newly designed kilns, fired by the eucalyptus we planted…

… to first dry in the sun…

All this in 2008 and with our own resources. As soon as the project was approved by the Bank, in 2009 we started the nursery and planted during the rainy months of that year.

In July 2009 all of the seedlings were in the ground!

… and one year later, results started to show!!!…

Immediately we prepared the new nursery for 2011, this time with 280,000 seedlings for 34 acres. And we used a technique absolutely new for this type of culture: insemination in tubes. So, we were able to focus on a much larger number of seedlings inthe same nursery space (larger irrigation controls, less manpower, monitoring of growth and fertilization) and, more importantly, we were able to plant them with greater ease and rapidity. We lost 3% of seedlings and we ended up selling the remainder to neighboring farmers. It was a beautiful design!

What put them in the ground… and we cared for them…

… and sprouted a multitude of fruit of the Conilon gene …

… while truck loads reached the processing facilities…

… that dried the coffee cherries at 80 centigrade…

all protected by the nearby virgin forest

We had many losses, almost 10%. Although it was expected, it left us a bit sad, but soon the flowering that came instigated us to move on quickly.

Anyway, we had learned a lot: next year we would have almost no losses. We moved quickly to build the shed, the workshop and all facilities as the crop in 2011 loomed huge!

We cared for the new plantation…

… full of cherries!!!

It gives you pride, does it not??

And up went the processing infrastructure! In the meantime, the plants never stopped to grow! … and grow …

… and harvesting was immense, grandiose, amazing…

… to be removed when they reached 12% of humidity and stored in a waiting stock shelter…

… with its dry hard shell to protect the beans from deteriorating. Then moved to our machine…

… to be deshelled and packed for shipment!!.

All this for one grain of coffee!!

All this for one grain of coffee!!

But as always, good things come to an end.

In 2012, the drought stepped in … el Niñoe … and it was bad.

We tried to save what we could by using the water from our two dams. We installed several pumps and almost 10 km of pipes, but it soon became clear that el Nino would not stop, and that the costs of maintaining the plantation in such conditions would be highly unprofitable.

We had to stop watering and we lost 20 hectares.

The rains returned.

2013-14 was a good year. The coffee plants recovered almost completely. Walking among the plants, we realized how tough the two years were that we suffered, but with all this delay of three years, the pruning process was vital to maintain the vitality of the plantation.

This means that we will have 40% to 50% of production in 2016, but in 2017 will become to produce between 50 and 60 bags per hectare.

Is fighting mad, as they say in these parts of the world, but that fight was beautiful!! And it is!

Short life-cycle crops

Wecall the short life-cycle crops those products that have a life span of maximum two years.

The ones wemare presenting are the results of the ‘natural selection’ of the ’innumerous’ other trialsthat occurred over the 12 years of our agricultural activity. These products ‘work’ in our microclimate, are or can be economically exploited in our kind of soil, have attractive local markets, areas that can be easily expanded if it needs to reach economic volumes, but can be started in small lots, with little investment and maintenance costs.

Last, but not least, there is enough in-house knowledge and experience to husband these kind of crops. Such knowledge is not trivial: there are many other interesting crops that could be considered, but new cultures must be studied, require experimentation, observation for at least a year or two, etc., before reaching a reasonably solid degree of their real potential of production and market viability.

For example, we already know what not to grow (with a minimal business objective) in this region: banana, pineapple, tapioca, cloves, are no, no, cultures. Just to name a few that we have experimented with and conclude on their economic un-attractiveness. Such conclusionsdid not come for economic reasons only: we looked at the climate, production, water needs, pests, processes, after harvest processing, market access, etc., just to start with. Those enclosed in this list passed all these tests. And soon we shall revisit them to select those crops that we shall add to the limes and coffee…

The produces that we shall consider in the future are:

The produces with a medium life cycle, are:

One could criticize (correctly) that our definition of short cycle crops is ‘unique’ to us. They would be right. Such selection is not only based on rational elements, but also on psychological, social and historical factors of the place. Maybe we should not separate such crops in to two groups… maybe the two cycles should be together and receive a more critical analysis … but it works for us and so … it is! (but can change.)

The pawpaw

We considered growing papaya in husbandry with the limes.

Pawpaw matures in eight to ten months and produces for two, max three years. Our manager, Wilson, had previous experience in growing this crop as a way ofbringing economic incomes rapidly, a sort of buffer while the limes trees mature to production: as a lime tree starts economic production in four years, papaya would supply needed funds for at least two of those years.

And so in 2010 we made our seedling from selected seeds and planted approximately 53 hectares.

Then we planted, and planted, and planted… for two solid months!

By September that year, we had 55 hectares of limes and papaya in the ground.

Toward the end of that year, we even made an emergency irrigation scheme, mainly to protect the pawpaw, as it is sensitive to the quantities of water offered. It was also a bonus for the limes, which need not such quantities, but grew faster than normal. And the pest control benefited both crops, and that was major economic factor: one shot for two birds sort of thing.

It was an excellent experience. In addition of helping our cash flow, we were amazed at the quality and flavor that these marvelous plants offered us. Not least Dona Lene, our comfort care-taker, who invented new ways of preparing papaws: from ice cream, sorbets, jams, meat curing, salads component, to papaya cream, a blended composition of ice cream and pawpaw with a touch of maraschino liquor!!!! Superb!!!

And as the papaya plants died in the second and third year, we left them in the field to decompose. In theory, we could have replanted until the fourth year, but the needs for sprayingsoon diverged for each crop, and the limes took priority: what for two years was good for both, in the third year became counterproductive. As the lime trees started to produce in the second and third year, in the fourth we could either spray papaya or harvest limes.

With the GlobalGAp certification and the severity of the inspections for MRL (Maximum Residues Levels) In Holland, we could not hesitate,

Also, pawpaw demands much more attention than limes, and maintaining such processes would distract us from our main goal of expanding the limes plantation and become independent. This same concern surfaced the following year when we planted maracujá, passion fruit, in husbandry with the limes.

The passion fruit, the maracujá

In 2011, with the accumulated experience of the papaw plantation, we decided to plant passion fruit in husbandry with limes, in the new areas of Peralba Rio and Peralba Nova Rio.

It was a success!!

Spraying and fertilizers matched perfectly and the plants received it with happiness: their growth was considered exceptional by our Wilson.

The exceptional growth of the lime trees was also due to the shadow that the passion fruit gave to the limes.

Husbandry of the maracujá crop was given to local farmers, almost all women, who literally enjoyed the pruning and …

… the human insemination techniques, all carried on while singing and laughing!!…

All in all, the passion fruit became an attractive product, easy to sell to wholesalers, but also to three supermarkets in Nazaré and Valença and Santo Antônio. In this way we kept costs down to a minimum.

Based on such success, in 2011 our Dutch partners became interested in planting this fruit to export to Europe. That meant allocating no less than 100 hectares to it… But… they demanded another kind, a reddish type, smaller than our, produced in and exported from South Africa, which had a very high acceptance in the European markets. Doubts abounded. So we decided to plant an experimental patch of five hectares.

The Dutch demand came for specially selected seeds, had to pass phyto-sanitary inspection by the Brazilian authority and when that hurdle was past, all seemed ready… but for a detail: the look of the fruit! If that shape, color and sizes were accepted in the European market, nobody would buy them here.

The equation was simple: with some 30% to 40% were of a quality historically acceptable for export (as in South Africa), we had no way to sell the remaining fruit in the local markets: nobody would be interested in buying. Also, the cost of convincing the public to accept these fruits, would have demanded a far greater effort than we were able or willing to make. In all honesty, the fruit considered acceptable for export looked… funny… when compared with our local quality!! (and we even thought of offering our kind for export, but abandoned such an idea almost immediately based on the knowledge of several failed trials made in the past by serious growers: our fruit does travel, is exceedingly sensitive to temperature and degrades rapidly).

Even while we were closing sales with supermarkets, we were swamped by intermediary buyers: we had all sorts of offers, from one-price-buy-all-production to one-price-per-single-watermelon to one-truck-full-price, paid in cash on the spot, or by weight, paid in second hand cars, in motorcycles, in promissory notes for the next five years. We even had a proposition that the buyer would pay on the promise of paying within a month, on his word that he never cheated anybody in his whole life. It was a funny gold rush! We went our fumbling ways, trying several methods to get rid of the left over fruit as we approached the end of the harvesting period.

And the more we ate watermelons, the more were coming!

In 2010, as this crop was growing, our Dutch partners, during their routine visit to the limes, marveled at the abundance and vitality of our experiment with watermelons, so much so, that they immediately contacted a major seed producer. The rep flew the following day from São Paulo to visit and one month later we received sample seeds from South Africa of the kind of melons that travel well and are commonly sold in Europe. We immediately planned to put in the ground seeds for five hectares and started to dream of 50 or even 100 hectares of this crop in the following years.

Unfortunately, we did not consider at that time the realities of the local market.

We evaluated (almost) all aspects and all seemed favorable: soil, water quality, access, facilities, infrastructure, personnel, the lot. On the basis of the soil analysis, we dimensioned the needs for fertilizers. If it was good for the watermelons, things should go even better for the melons, as they were touted as more resistant to pests and to dry weather. And it did. We planted all four kind.

Wetried! We even looked at markets as in São Paulo, where people traveled overseas and would be more receptive to this new kind. In the supermarket where we placed fruit to experiment, none were sold. Disastrous. The economic equation would not close: in partnership with limes it made sense and brought a profit, alone… no way.

And so we had to abandon our experiment and our dreams of a special new crop.

We ate lots of funny looking passion fruit in 2012 and 2013!!!

But, for us, selling on the local market, the maracujá plantation in consortium with limes, was a success!

The net results of all this effort were huge watermelons, delicious, blood red inside, huge.

80 tons per hectare! We went directly to the supermarkets and sold it all. Had we double, we would have sold three times… nice.

And we had our crop of surprises: bank check without funds, truck loads that disappeared (mostly paid in advance), weights that shrank at the weighting station, complaints that a load arrived all broken and that not a watermelons could be sold (and could we please replace such loads…) and so on.. but having to distribute 80 tons of fruit per hectare of a fast deteriorating product focused our attention and forced us to be creative in sorting out propositions: the fruit had to be sold.

All in all, it was fun! Profits paid nearly six months of salaries, but it certainly made us aware of the dynamics of this culture.

Again, the results were outstanding: excellent fruit, right color, right weight, right skin, right brightness, right taste, right everything.

We started to get ready for the next step of 50 hectares… was it not for a small detail… two actually, but the first could have been solved somewhat easily:short production enveloped and no local market.

One characteristic of our climate is a rainfall between 1.600 e 2.400 mm, fairly well distributed during the year. Ideal for lime and also for melons, but, in the winter months from April to August, there are lots of clouds and light is strongly reduced. During those months, growth slows and this reduces the maturation period of melons. We call this a restricted envelop. This situation can be expanded substantially by choosing the right months for planting and inducing a fast growth with emergency irrigation. A can do situation.

Water melons and melons 2010 and 2011 were experimental years. The limes elevated to principal crop, pawpaw and maracujá, passion fruit, in husbandry with the limes, coffee growing happily in a secluded part of the farm… and now came the idea of a trial patch of watermelons in between the lines of passion fruit and limes, to expand eventually into separate plantations as the results allowed it.

We actually had two opportunities with this crop: the watermelons for the local market and the specialty melons for export.

Again our field marshal, o Dr. Wilson, was heading the conception and execution of this new program. We needed all his experience and leadership, as the watermelons, and later the melons, were planted in between the limes and the maracujá! And for eight months all three crops lived together in an area of some 20 hectares, dodging spraying and fertilization processes, till we harvested watermelons and maracujá in synchronism. The positive results we got were exclusively due to the husbandry of our heroic Mr. Wilson!

And in this period we had watermelons for breakfast, lunch and dinner!

We went through all this theater for two years. In 2012, the limes and maracujá madeit impossible to take care of the watermelons in between them.

We planned to plant more in 2013, when the 2012 draught hit. Lucky us, as this product disappeared from the tables of Salvador that year.

Alba loved the whole process!!

What killed the project was the inexistence of a market for such new produces: all the supermarkets our clients tried to sell our melons to did not want to buy them. It was unknown,and lookedupon with suspicion, as they were smaller than the traditional watermelons. The cost to introduce a new product and be accepted by a reasonable number of buyers put off all distributors and supermarkets. We found out that Brazilians in Salvador are not famous for experimenting with new fruit.

As between 50% and even 70% of this fruit would not be of export quality, it became quickly evident that, with prices practiced in the EU and the inability of distributing the excess production in the local market, the economics of the venture would be

substantially negative.

Same response as the maracujá.

Sad, because it all had to be a success.

Then, in 2016, at the time of this writing, things started to change: today we can find these melons in several upscale supermarkets in Salvador and in some specialty shops. That means that someone did have the wherewithal to produce and stick to the product.

In São Paulo, apparently the acceptance of this kind of melons increased substantially in the last years and their offer is more diffused.

Who know that sometimes, soon, in the future, we shall not revisit such a project?!

Ornamental flowers

We planted ornamental flower for only one season, but its results were so enticing that we are relating them with an eye to a possible future for this produce.

We planted ornamental flower for only one season, but its results were so enticing that we are relating them with an eye to a possible future for this produce.

In 2013, Dr. Vernon Aaron, a researcher in biology at the University of Irvine, in California, visited us with our good friends and sponsor of the planting of the music trees project, Dr. James Gardner and Dr. Anne Breuer-Gardner. As good biologists do, he went in the most recondite places of the forest, the ones that are so thick and dense that at 2pm it seems is night on the ground, so thick is the trees canopy there. And he came back all exited, that he found an unknown flower, the same as his photo, here below.

When we told him that often we find such flowers growing in the fields and that we sort of consider it a nuisance, he became even more interested and asked if we were interested in growing this flower on a commercial basis. We responded with doubts and concerns, that to do so we would need men trained, economic quantities, packaging, sales overseas… etc, the usual óh boy what is this guy asking us to do’ syndrome. He did not give up. He asked for the permission to plant in a small lot near where he found the flowers. He was serious!

Detailed negotiation ensued: he would be the only responsible one for it, pay and train the worked dedicated to it, harvest, pack, sale, ship, the whole thing, in his hands. He accepted. We cleaned one hectare for him. The he went to work.

And so he planted.

Every month he endured the 20+-hour plane trip to visit the patch. Six month afterwards, strange looking cartons arrived with Dr. Aaron en-suite. He packed, loaded and shipped some 2348 cartons back to the States. He cleaned the patch, replanted the small growth that was cleared, left as if nothing had happened there. He told us he had made a small fortune with it. We received as thanks, a wooden box with 24 bottle of old whiskey.

I passed by recently and I could see no trace of the exploit. Maybe a couple of flowers that grew in spite of his cleaning up.

It gave us a sense that we missed something. That maybe, maybe, we should have looked at this forest produce with more care, that there is a lovely business in it… we’ll see.

Medium life-cycle crops

We call medium life-cycle cropsthose produces that have a life span of more than two years.

The ones presented are the result of the ‘natural selection’ of the ’innumerous’ other trialsthat occurred over the 12 years of our agricultural activity. These products ‘work’ in our microclimate, are or can be economically exploited in our kind of soil, have attractive local markets, areas can be easily expanded if theyneed to reach economic volumes but can be started in small lots, with minimal investment and maintenance costs.

And last, but not least, there is enough in-house knowledge and experience to husband these kind of crops. Such knowledge is not trivial: there are many other interesting crops that could be considered but new cultures must be studied, require experimentation, observation for at least a year or two, etc., before reaching a reasonably solid degree of their real potential of production and market viability.

For example, we already know what not to grow (with a minimal business objective) in this region: banana, pineapple, tapioca, cloves, are no, no, cultures – just to name a few with which we have experimented and concludedthat they are economically not viable. It was not only economic reasonsthat led us to this conclusion: we looked at the climate, production, water needs, pests, processes, after harvest processing, market access, etc., just to start with. Those listed below passed all the above tests.We shall look at these again, in the future, to select those crops that could be added to the limes and coffee…

Theproduces that we shall consider in the future are:

- Pawpaw

- Passion fruit

- Watermelons and melons for export

- Piassava

- Ornamental flowers

- Eucalyptus

- Cacao

- Acai

- Cloves

- Dendê

- Rubber trees

Our crops: the medium life-cycle produce

- Eucaliptus

- Cacau

- Açaí

- Dendê

- Seringa

One could, correctly criticize our definition of medium cycle crops as ‘unique’. It is not only based on rational elements but also on psychological, social and historical factors of the area. Perhaps these crops should not be divided into two groups… maybe the two cycles should be combined as one and there should be more of a critical analysis. However, it works for us but we are not averse to change if necessary.

The eucalyptus business

When we planted the first 10 hectares of coffee, we became aware that drying it would be a major procedure forthis produce.This would allow us to stock it for long periods (even as long as 12 to 24 months), and sell it when theprice was high… if cash flowhad not been an issue.

At the time (2007), we were contemplating a sophisticated processing plant, somewhat expensive, but we discovered a large amount of wood had to be used for the process. We feared we would have to cut trees from the forest to match the demand for fuel, which would be anunconscionable idea! Nonetheless, we went ahead and planted 35 hectares of eucalyptus, just to be sure.

The eucalyptus business

Then our Doctor Matiello, recognized internationally as the absolute authority in coffee (the ‘pope’ of coffee), in partnership with other researchers, designed a new way to dry coffee with a kiln which would be cheap to construct and use minimal fuel. We immediately changed plans, constructing 3 kilns and, in 2008, we had the whole process ready for that year’s crop. Thenet result was that instead of 30 tons per harvest, we needed only three! But the trees were already cut so… now we have 35 hectares of eucalyptus to sell… andmaybe we can even expand and include this crop!

The cacao business

When we bought the PeralbaFloresta group of farms, we foundthat there were already three existing hectares of cacao – abandoned, miserable, but alive. Two years later, in 2009, they began producing 35 arrobas per hectare. We were so proud that we started scouting for other areas and we planted approximately another 10-12 hectares, in remote sites of the farm.

Then we discovered that the work force costs to maintain such crops, were prohibitive. Today, we still have about 9 hectares producing and the fruit isharvested by our faithful Louro, 50% for him and 50% for us. Not much, but the cacao is still there.

We learnt though that in the last 15 years, cacao has been grown in husbandry with seringa, the rubber tree. This is where we shall go next, as soon as the lime business consolidates.

The acai crop

In 2010 we planted two hectares to experiment with his crop, near the Yellow House, more as a curiosity than a real intention. The growth was so energetic that we planted another couple of hectares in another wet area, far away, and left it to grow unattended. Same result: exceptional growth, total resistance to pests, no fertilizer, no husbandry, nothing. As this palm grows in very humid environments, of which we have plenty around the farm, why not fill those remote areas with this crop? We estimated that we might fill 30 or 40 hectares in various sites. Harvesting could be done in partnership with some local, a la piassava, and costs would be kept at a minimum. Several smashers confirmed their interest in buying all we could produce… small income in comparison with limes, but nice to have, without all the headaches of a full plantation of this produce. As soon as we get the limes stable, we shall revisit this crop. 2019 would be about the right time for this.

In 2010 we planted two hectares to experiment with his crop, near the Yellow House, more as a curiosity than a real intention. The growth was so energetic that we planted another couple of hectares in another wet area, far away, and left it to grow unattended. Same result: exceptional growth, total resistance to pests, no fertilizer, no husbandry, nothing. As this palm grows in very humid environments, of which we have plenty around the farm, why not fill those remote areas with this crop? We estimated that we might fill 30 or 40 hectares in various sites. Harvesting could be done in partnership with some local, a la piassava, and costs would be kept at a minimum. Several smashers confirmed their interest in buying all we could produce… small income in comparison with limes, but nice to have, without all the headaches of a full plantation of this produce. As soon as we get the limes stable, we shall revisit this crop. 2019 would be about the right time for this.

The dendécrop

The dendê oil is an edible vegetable oil, derived from the monocarp (reddish pulp) of the fruit of the oil palms, primarily the African oil palm Elaeisguineensis.

This palm oil is a common cooking ingredient in the tropical belt of Africa, Southeast Asia and parts of Brazil. Its use in the commercial food industry in other parts of the world is widespread, because of its lower cost and the high oxidative stability (saturation) of the refined product when used for frying.

Most recently, it has been used in producing diesel oil for cars and trucks, bio-diesel, and is sold directly to the public via distributors like Shell and Petrobras.

Dendé needs vast areas to become economically viable and, for this reason, it will remain a minor/social crop to be harvested by our loyal Louro and sold to the local smasher. He is a direct descendent of freed slaves and runs an extended family in a nearby area called Mata Escura. He is a neighbour of great value and presence, for whom we have great respect and affection. He and some members of his family (which includes his mother of 75 years of age) work at various times, under contract, in our coffee plantation. Ourdendé is totally harvested by him and we take a small cut to establish ownership. The rest is all for him.

Let’s call this our social investment in a precious neighbour.

The natural rubber crop (in husbandry with cacao)

This was one of the first crops with which we experimented. Itrelies on the vicinity of Michelin, the tyre company, while a family member was the production director. We were allocated 30 hectares,but planted only 2,4, just to experiment. We discussed at length whether to plant in husbandry with cacao, but eventually decided that the experiment had to be seen isolation. Only in this way, would we be able to gauge the real needs and difficulties of such a crop.

It went well. However, we got distracted by the cattle business and later by the lime business. The site was eight km from the Yellow House and the people we recruited from the south, experienced in rubber plantation,were not happy to live in the primitive situation of the rubber farm (no electricity, no way to link it, no running water, no television, no fridge, difficult transport to school, just to start with…). It was a no go situation. When the trees started to produce, people left. We had to give up this project, which was very sad.

Since then… the road reaches the house, electricity is nearby, the school bus picks up kids from farms further away… it became livable, too late though.

The concept was a success: perfect climate, perfect soil, perfect area. Whatwe need now is enthusiasm and youth to reactivate this project, start anew, with cacao en suite, a new house with all amenities… and 30 to 50 hectares to make it sustainable.

We are ready… as soon as the limes consolidate…

The Atlantic Forest

The Atlantic forest covered an area of 1,315,460 km2 and originally spanned 17 Brazilian states: Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina, Paraná, São Paulo, Goiás, Mato Grosso do Sul, Rio de Janeiro, Minas Gerais, Espírito Santo, Bahia, Alagoas, Sergipe, Paraíba, Pernambuco, Rio Grande do Norte, Ceará and Piauí.

Today only 8.5% patches of over 100 hectares remain. If one adds together thepatches of native forest above three hectares, the remaining cover is 12.5%. TheAtlantic forest is a world hotspot, one of the richest biodiversity areas in the world… and one of the most threatened. To protect what is left, many of the remaining areas have been declared as Bio-sphere Reserve by ENESCO and wereelevated to the rank of National Asset in the Brazilian Federal Constitution in 1988.

The original composition of the Atlantic Forest is a mosaic of different kinds of vegetation, namely: dense, open and mixed ombrophily forest, deciduous and semi-deciduous seasonal forest, high level fields, swamps and ‘restingas’.

72% of the Brazilian population, today, livesin the Atlantic forest area, according to the IBGE (InstitutoBrasileiro de Geografia e Estatística) findings in 2014. That means that some 145 million people inhabiting 3429 municipalities, are situated inside this area, while 948 are located at its border (IBGE, 2010).

The bill that was sanctioned in the Mata AtlânticaLaws, provides rules as to how the remaining forest and natural resources are to be managedand used. After moving through Congress for 14 years, it became law in 2006.

As a consequence, Brazil today, has over 1100 RPPNs (ReservasParticulares do Patrimônio Natural – Private Natural Reserves of the National Asset). Over 760 are located in the Atlantic Forest, also for the protection of endangered species: of the 633 declared for protection in Brazil, 383 live in the Atlantic Forest.

The WWF divided the Atlantic Forest in 15 eco-regions with the objective to preservethe species of flora and fauna, through specific actions relevant and appropraite for each region with similar biomass. The biodiversity of this forest is similar to the one in the Amazon, probably much more diversified due to the variations in altitude and longitude of the forest vs the Amazon.

The Atlantic Forest is an immense endemic centre and its vegetation formations are extremely heterogenic, branching from open fields of the semi-arid ‘caatingas’, impassable mountainous regions, down to rainy areas in the low lands and near the ocean swamps. The fauna, too, is endemic to innumerablespecies, several with animals native to this land, like the mico-leão-dourado(Leontopithecusrosalia) or the onçapintada (pantheraonca)

There are numerous additional subdivision of the biomass, be it for different climactic conditions, recuperation zones, altitude areas and human contact-tension zones. The interface with each area creates unique conditions for diversity in flora and fauna.

Recent studies indicate that 39% of mammals are endemic; and so are 160 species of birds and 183 of amphibious animals.

In terms of flora, 55% of the arboric species and 40% of the non-arboric ones, are endemic to the Atlantic Forest. 70% of the world bromeliads and orchids can be found in this habitat, only. 64% of the palm species are from this region. In all, over 8000 vegetation species are endemic in this forest.

In the Atlantic Forest, today, the following known species can be found:

More than 20000 species of plants, of which 8000 endemic

270 of mammals 992 of birds

197 of reptiles 372 of amphibious

350 of fishes

Where the Peralba is situated, there are two major kinds of biospheres:

Ombrophily forest of the coast of Bahia

Coastal swamps

FlorestaOmbrófilaCosteira da Bahia

The Ombrophily forest of the coast of Bahia is an eco-region in the Atlantic Forest that extends from the limits ofthe Sergipe State, down south to the north of the Espirito Santo sSate. Its width from the coast, varies between 100 and 200 km and the area is approximately 110,000 km2.

It is a major endemic centre for all species, of which many are in danger of extinction, like the tree of pau brazil, or the mico de caradourada, preguiça de coleira(Bradypustorquatusor sloth).

Biodiversity This is the most important endemic region of the whole Atlantic Forest, characterized by an extremely rich bio-diversity. There are 12 species of primates or 60% of such species for the whole Mata Atlantica. Notable are the mico-leão-de-cara-douradaand themacaco-prego-do-peito-amarelo. Birds are so varied that 50% of all speciesof the Atlantic Forest are present here. UNA, a town nearIlheus, was evaluated as having the highest density of fauna and flora per hectare of the whole region.

Characteristics These swamps constitute separate areas, mainly on the estuary of rivers, particularly the Rio Doce in the State of Espirito Santo. The climate is humid and can reach 2600 mm per annum of rainfall. There are three types of swamps: Rhizophora Avicennia and Laguncularia

The Coastal Forests of Bahia are set in a eco-region of the most rich Atlantic Forest in Brazil. This extends from Salvador, down the whole coast of the state, until thenorth reaches of the Espirto Santo state. This regionstretches from approximately 100 to 200 km from the coast and its area is as big as 110/130 thousand km2.

This is one of the most threatened areas in the world, as only 5% of the original forest still exists.

Conservation The region, particularly the Mesa-region of South Bahia and the Reconcavo (where the Peralba is situated), has, for centuries, been a producer of cacao and, as a consequence,the original forest was preserved, as the cacao plants grow in the sub-Bosque. For this reason, 7% of the original forest cover still exists. Unfortunately,local farmers own the majority of such lands, whichmakesit difficult to protect what is left.

In the south of Bahia, there is a mosaic of protected areas that totals approximately 500km2, while the ReservaBiológica de Sooretama e a Reserva Natural Vale adds another 440 hectares.

The importance of such an ecosystem is put intojeopardy by the ongoing devastation and eco-corridors that have been built in numerous parts. A project to create an eco-corridor to link some 86000km2 is under way; it will link Bahia to the Espirito Santo State.

Conservation The Bahia swamps are under strong anthropic pressure as they coincide with densely populated areas. Little has been done to protect this vital environment and the few initiativeshave barely left the project phase.

Characteristics In this region, the predominant phytol-physiognomyis the dense ombrophily forest with formation of ‘restingas’ (coastal enclaves) and swamps on the coast.

In the forest, trees reach 35 metresor more. It is the stretch of Atlantic forest most similar to the Amazon, particularly below the Reconcavo, the area where Salvador is located (the Peralba farm is 68 km south from Salvador).These forests, known as Mata do Tabuleiro (forest of plateau), are seasonal semi-deciduous – those that one sees in films, with numerous lianas reaching for the ground.

The climate is hot and humid withannual rainfalls between 1200 and 2400mm. There is a mild dry season between September and December in the north part (where the Peralba lays) and May to September in its south.

Mangues da Bahia The swamps in Bahia form a region of some 2000km2and form part of the Atlantic Forest (the yellow patches in the image). They represent swamp areas on the coast line. This is by far the most endangered ecosystem of the Atlantic Forest.

The Peralba Atlantic Forest

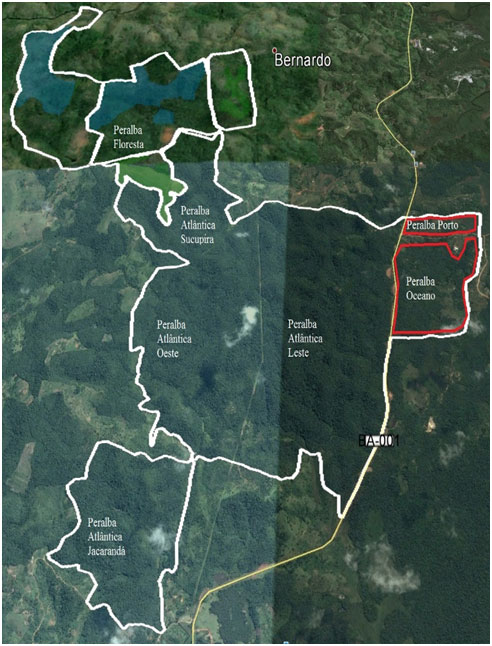

A study carried out by a researcher from Ceplac, Dr. Paulo Reis, defined our forest area as possessing two distinct bio-physiognomies: Coast Ombrophily Forest of approximately 1800 hectares and Bahia laguncularia swamps

The first phytol-physiognomy has three areas connected:

ThePeralbaFloresta, which has around it the plantations of lime and coffee (+/-350 hectares)

To the south, the Peralba Sucupira, the first of three conjugated areas of PeralbaAtlanticaLeste e Oeste (+/-1.100 hectares)

At the extreme south, thePeralbaJacarandá,approximately 550 hectares.

The second bio-physiognomy is composed of coastal swamps divided into two distinctareas:

ThePeralbaOceano, historically dedicated to pasture, is now growing back since we came in 2005. It is returning to its original primal state of being a mangrove of the laguncularia kind.

A Peralba Porto, with swamps of the avicennia kind. The house of the Coronel Viannastill stands here at the old port of the farm

We preserve all these areas with great care and strong discipline.

The Peralba Rivers

Peralba is blessed with numerous rivers and perennial springs.

Peralba is blessed with numerous rivers and perennial springs.

Situated on the first boulders of the continental shelf, Peralbais abound with water all year long. We never run out of water. This is a good omen, in fact a golden present from the skies, as till the day we did not have a real need for irrigation. (well, besides 2012-13 when the El Niño hit us heavily). For that reason,in 2017, we shall introduce an emergency ferti-irrigation scheme, not to caught off guard again.

The widest of the rivers is the Rio da Dona. We have only one mile of this river, but it is immense, particularly during the rainy season, when the water flow expands tenfold.

The most important or intimate, for us, is the Tirirí. It runs through most ofthe farm from north to south on the western limits of the propriety.The origin of its name refers to aYoruba deity, Exu, later reincarnated as a Candomblé divinity: from Esu in Nigeria to EXú in Brazil, this deity, this ‘orixá’ was transformed from the creator of the world to the divinity that brings communication, patience, order and discipline (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eshu and https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exu_(orix%C3%A1) ). To us it brings pure water. The Tiririis born a few miles from our landsand crosses no city or village. It reaches the ocean after feeding its waters to our swamps.

It is a kind of spinal cord that also sustainsour Mata AtlanticaOeste and receives the water from two other streams that start in ourfarm: theSucupira River and the Urubu River

On the north side, we have our riacho(a perennial stream of minor size)Peralba, born from two wells at the upper limits of the farm and feeding the plantations of limes and coffee.

In the PeralbaAtlanticaLeste, the riachoPeralbaOceano is born and feeds the swamps creating a mini ‘laguncularial’and ‘avicannia’ biospheres.There is the PeralbaPort, giving us access to nearly 120kmof swamps and mangroves and immense estuaries.

Each river is described in more details:

The Tirirí, its rapids and its waterfalls

The Rio da Dona

TheriachoSucupira (ouMãe Bernarda)

TheriachoJacarandáand the Urubu waterfall

The riachoPeralbaand the lagoon of the Jacaré (Alligator)

TheriachoOceano

The Tirirí, its rapids and its waterfalls

The Tirirí is borne some 6 to 8 km from the farm, out of asmall spring set in a deep valley. The main feeder is a couple of miles from our farm, and is protected by a farmer much concerned with ecological issues.

Such abundance reflects on the animal andplant lives: is not uncommon to see bucks frolicking at the river early in the morning, while monkeys and micosleõesstand by. Numerous pools festoon the meanderings of the river and they were occasional swimming places in times past, right at the beginning of the Peralba. Today, with all the commitments with the business, we seldom visit these sites, but we made sure nobody is disturbing their peace.

The water flows year round, but the Tirirí is subjected to the vagaries of the weather. In the rainy months, the flow raises to some 30m3 /sec creating immense rapids and feeding three immense waterfalls. During draughts, a flow of five to seven m3/sec is normal.

After this, things calm down. The river has reached the sea level and is now feeding the immense swamps that reach close to the ocean.

In both cases, the effect is magnificent: t in the depth of the forest, under immense canopies, the river creates an oasis of pleasure, be it with roaring waters or with calmer and more intimate flows.

However, the best parts of the river are when the water reaches three falls. Still under majestic trees, the water transforms the place in atourbillion of pure energy. With a span of 32 to 44 meters (100 to 140 feet), we had to intervene to save the young lady who dared to defy the shoots.

TheRio da Dona

The northern upper reaches of the farmare bordered by the Ria da Dona.

This is a 150 km long river, and passes through several villages and cities. The last one Santo Antonio do Jesus, is 50 km from the farm. There the water is collected in a big lake to feed the town with water.

Our border is relatively short, no more than a couple of miles. When it leaves our lands, it passes by São Bernardo and goes to feed 12 miles of swamps before becoming a one-mile wide estuary to the ocean.

It is a major river, one that feeds water to maybe 300,000 people in the upper towns and sustains several colonies of fishermen on its immense estuary (more than a mile wide).

We had plans to use its water to irrigate the limes plantation during dry months: its supply of water is always abundant, even in the most stringent months of 2012. Maybe in the future…

We have a workers house down there, and we always thought of transforming it into an ‘advanced’ post for meditation… but that will have to wait as well…

And the river gives more: past the swamps, when near the town of Jaguaripe where it expands to well over a mile wide, anglers practice fishing of Robalo! People who know, know what this means!!

TheriachoSucupira (orMãe Bernarda)

The riacho Sucupira (a perennial stream of minor size) starts in two springs in the Peralba Sucupira limes plantation, right at the limit of the new crop. The water is so pure that it tested as mineral water. These two wells, and other on the other side of the hill, have been used for centuries by locals to get drinking water. They will be well preserved uas long as we shall be around!

Its path meanders in the very thick of the Peralba Atlanticas, in fact it sort of divide the two areas. It is a succession of pools, waterfalls, and calm ponds, under the thickest canopy you can get from of our Mata Atlantica. It eventually ends in the Tirirí, in a magnificent pool just after the three major waterfalls. Lovely. Our jewel!

With some eight km of extension, by following it one can admire the forest at its best. For nearly 10 years now (since 2005) nobody has cut a single tree and the forest is closing all gaps that wood hustlers did open while robbing the place of the best wood. But they went no further. It takes 20 to 30 years for such places to recuperate fully to its primal state. For 10 years the forest has been recuperating. We need 10 or 20 more years.

The upper branch passes by the Mãe Bernarda ruins of her ‘quilombola’, her former house. In the local lore, even before the freedom of the slaves in 1888, this woman, a shaman, was performing births and cures to the local galera where slaves were raised to be sold. She is venerated today by several elders who still speak of her as a powerful lady of immense courage and skills, who, for 50 or more years, till the 1930s, brought relief and refuge to humans whose only fault was a dark skin! A light of piety in an otherwise cruel world. But this is past. Today all this lore is just a memory that instills courage and self-respect to those descendants from slaves that still fight for a living in this area.

Then the riachoSucupirapasses through the Paradise Valley. Enclosed in a deep gorge, with a thin waterfall at its north entry,the riacho opens up to a small area populated by numerous animals: monkeys, parrots, even some jaguars. And naturally scorpions and snakes and devouring ants… but we shall leave that to the more courageous of visitors.

The riachoJacarandáand the Cachoeira do Urubu

A second jewel hidden in the forest and still little known to the world is the Cachoeira do Urubu, the Urubu waterfall. The name derives from a big bird, the Urubu da cabeçapreta (Coragypsatratus),a kind of vulture endemic to this place, that flies very high in the sky and controls the approaches to its domain from afar.

This riacho is born within the farm,and some four km upstream the main shoot crosses the high reaches of the Peralba Jacaranda area through one of the most dense and intense patches of our forest, before falling 60 meters down.

So thick and closed is the forest up there, one can walk through only by wading in the stream: to walk under the canopy would demand two ‘batidores’ who would open a path with their machete to get through. So thick is the vegetation, that some people become claustrophobic! The density of trees and of the thick under-growth creates a sensation of being enclosed in some strange animal or exotic land with myriads of unknown dangers!

Atlantic forest at its tremendous experience for those who appreciate such environments. The riacho falls down some 60 meters (140 feet) into a lovely pool almost at the level of the sea.

We left the access to it all very difficult, hard and uncomfortable to find. In 2005 when we arrived, people had cut a trail and picnicked there, leaving trash and cutting trees on the way. In 10 years, the path is almost invisible and the two km access from the road near the Tirirí to the waterfall is hard to find. With the demise of the small bridge, the access is now almost impossible to weekend visitors: only the most loyal forest lovers do the trek today. And it will stay like this until we shall open it and allow disciplined access to this beauty.

We brought this place back to it pristine and immaculate state by simply leaving it alone. We shall be back in due time and with due care.

The RiachoPeralbathe Lagoon of the Jacaré (the Alligator lagoon)

TheriachoPeralbais our river… or better, our riacho.

It is born from two wells 8 km into the farm, right where the plantation of limes is, in the Nova Rio area. And it goes through all ofPeralba Italia and then passes by the Yellow House.

Just after the springs (more wells, as the rogation of water is around 1m3 per minute), the riacho forms a sizable lagoon of some 500m X 120, the Nova Rio lagoon. We have thought of using this water for irrigation, but balked at the laws that govern such projects. Maybe in the future we shall return to this and carefully use such abundance.

Then theriacho coats the whole of the Italia plantation and forms another lagoon, the Italia lagoon, before descending nearly 200m through small waterfalls and numerous pools that we use to batheand swim in. A small wall near the Yellow House provided us with fish and prawns for many years. Today the frantic pace of the lime business has left such endeavors on the side. Who knows one day we go back to them…

Then the riacho feeds a marvel: the Jacaré lagoon. With the size of 500m X 200m and encrusted inside heavy trees, the lagoon was home to a couple of alligators that terrified the neighbors until a bad guy killed the female, who knows why, as the penalty if caught would have been severe indeed. But such are the things of life. The male alligator eventually left the water to seeka new companion, only to be run over by a truck. Sad. We have asked a nearby grower of such animals to replenish our stock and revivethe place, but bureaucratic issues impeded that to date. It will be done soon. Promise.

The riachoOceano

This riacho is almost unexplored as the access is impervious, set in a deep gorge, and seldom we go that way.

I think we went there maybe three times in all these years. In the last visit, we took this photo.

It’simportance for us is that it cuts across the plane and waters in the Peralba port before losing itself in the mangroves.

It almost certainly provides water to the Coronel Vianna house, which is still standing. When the eco-tourism project will be initiated, we shall start from here first by recuperating the house and the port.

The Peralba flora and fauna

Some time ago, in 2006 or 2007, we asked a known researcher to doaninventory of the flora and fauna of our forest. We wanted to know what we had bought as everyone was saying it was a fantastic piece of forest and had immense ecological potential. So they said.

Back came the proposal: 1 million Reais, US$450,000 at the time, and two years of work. Immense.